The National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) was first introduced in 2008 as an assessment for the following domains: reading, writing, spelling, grammar and punctuation, and numeracy; for students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9.

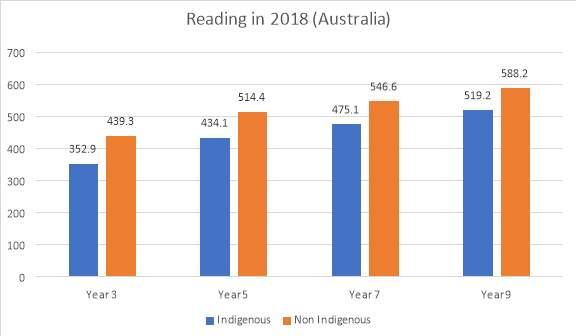

Figure 1 Mean scale score

As displayed, a similar pattern could be seen across all five domains in each of the states in Australia. This trend has also been reproduced every year from the start of the NAPLAN (ACARA, 2018).

The demographic of indigenous young adults plays a primary contributory factor, where only about one third of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people lived in Major Cities of Australia, compared with around three-quarters of the Non-Indigenous population (ABS, 2018). For those living in the rural and regional communities, exposure to Standard Australian English (SAE) is rather limited prior to formal education. Growing up in an environment of traditional languages and English-based creoles [of which there is at least 250 known distinct Indigenous languages (AIATSIS, 2005)] , they become circumstantial bilinguals, learning a second language out of necessity (Valdes, G. & Figuero, 1994). This was exemplified in the 2011 Census reports where 83% of Indigenous Australians speak English at home, but a majority of them uses a distinctly Aboriginal form of English that differs from the SAE used in educational settings (Hall, 2013; Eades, 2013). A problem arises when standardized tests normed on populations of only English speaking backgrounds are used (Genishi & Brainard, 1995; Thomas & Collier, 2002). Mastery of a sentence like “He likes apples” is an achievement for someone who speaks SAE as a second language, but is trivial for one who uses SAE as a first language. Derivatively, poor grades do not represent poor cognition nor inadequate linguistic competence, but will consequentially result in limitations of future life options.

A key to developing core skills in education is the minimization of disruption to formal education. Although there is a paucity of studies, but the available data on the school attendance and retention rates (defined as proportion of students who continue studying to a certain year) is sufficient to establish a statistically significant gap between the indigenous and non-indigenous students. Independent of their age, Indigenous students consistently have poorer attendance and retention rates from Year 1 to 10 (Nola & Sarah, 2010). This problem is multifactorial and among them includes parental-condoned absenteeism, society insufficiently valuing education, inadequate welfare support especially in the early years of schooling, inconsistent approach to absenteeism among schools, unsuitable curriculum for some pupils, local unemployment, poverty, etc (Reid, 2008). Approaching this problem from multiple angles would be the key feature in reducing the issue as this has been identified as the most important feature accounting for the disparity between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous literacy and numeracy outcomes (DEST, 2006).

Among populations of different socioeconomic (SE) backgrounds, literacy gaps already exist prior to the initiation of formal education. In 2014-2015, the proportion of Indigenous adults in the lowest income quintile was twice compared to non-indigenous (36% vs 17%). Employment rates were similar with only 48% of Indigenous adults having employment while it was 73% for non-indigenous (AIHW, 2017). Fundamental skills pertaining to reading acquisition such as phonological awareness, vocabulary, and oral language were less likely to be developed among children from low-SE families (Buckingham & Beaman-Wheldall, 2013). Initial reading competency is greatly correlated with the home literacy environment and book resources (Aikens & Barbarin, 2008; Bergen, Zuijen, Bishop & Jong, 2016). A positive literacy environment stemming from access to learning materials and experiences, including books, skill-building lessons or tutors are less likely to be found in a poor household (Bradley, Corwyn, McAdoo & Garcia, 2001; Orr 2003). Academic skills develop slower among children from low-SE households and communities, with an association with poorer cognitive development, language, memory and socioemotional processing (Morgan, Farkas, Hillemeier & Maczuga, 2009).

As a conclusion, the factors explained above only represents a few major factors to why Indigenous students underperform in NAPLAN. The path to approximating the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous students remains a long one. As front liners, educators play a significant role in the mitigation of this problem.

References:

- Aikens, N. L., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Socioeconomic differences in reading trajectories: The contribution of family, neighborhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 235-251.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2018). Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016. Retrieved date July 27, 2019, from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3238.0.55.001

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). NAPLAN Results. Retrieved date July 27, 2019, from https://reports.acara.edu.au/Home/Results

- Australian Department of Education, Science and Training (DEST). (2006). National report to Parliament on Indigenous education and training, 2004. Retrieved date July 27, 2019, from https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A37322

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). (2005). National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005. Retrieved date July 27, 2019, from https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/products/report_research_outputs/nils-report-2005.pdf

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2017). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Performance Framework 2017 Report. Retrieved date July 27, 2019, from https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/indigenous/hpf-2017/tier2/208.html

- Bergen, E., Zuijen, T., Bishop, D., & Jong, P. F. (2016). Why are home literacy environment and children’s reading skills associated? What parental skills reveal. Reading Research Quarterly, 52, 147-160.

- Bradley, R. H., Corwyn, R. F., McAdoo, H. P., & García Coll, C. (2001). The home environments of children in the United States Part I: Variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Development, 72, 1844-1867.

- Buckingham, J., Wheldall, K., & Beaman-Wheldall, R. (2013). Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: The school years. Australian Journal of Education, 57, 190-213.

- Eades, D 2013. They don’t speak an Aboriginal language, or do they?, from Aboriginal ways of using English, Aboriginal Studies Press: Canberra, ACT, pp. 56-75.

- Genishi, C. & Brainard, M. (1995). Assessment of bilingual children: A dilemma seeking solutions. In E.E. Garcia & B. O’Laughlin, (Eds.), Meeting the challenge of linguistic and cultural diversity in early childhood education (pp. 49-63). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Hall, J 2013. Communication disorders and indigenous Australians: a synthesis and critique of the available literature, Honours, Bachelor of Speech Pathology (Honours): Edith Cowan University.

- Morgan, P. L., Farkas, G., Hillemeier, M. M., & Maczuga, S. (2009). Risk factors for learning-related behavior problems at 24 months of age: Population-based estimates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 401-413.

- Nola, P & Sarah, B. (2010). School attendance and retention of Indigenous Australian students. Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Orr, A. J. (2003). Black–White differences in achievement: The importance of wealth. Sociology of Education, 76, 281-304.

- Reid. (2008). The causes of non-attendance: an empirical study. Educational Review, Vol. 60, No 4, 345-347.

- Thomas, W. & Collier, V. (2002). A national study of school effectiveness for language minority students in long term academic achievement. Final report. Washington DC: Centre for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence